A photobook is a time-traveler; at once attesting to an event and moving away from it, both temporally and spatially. Think of this movement as a spiral, where the lived experiences of the bookmaker and those of the subject (s) of the book coalesce at its hub. As the spiral unwinds, the sequenced images affect those who are much more remote from the catalyzing events at its core very differently. Ever-widening distance from event to viewer means that images representing traumatic events are exposed to a more detached spectatorship, “terror packaged as entertainment” (Kijowski, J. 2016. 195)

Ulrich Baer describes our fascination with images of traumatic experiences as deriving in part from the degree of difficulty in relating to the extremity of the event and its impact on those it acted upon.

“The viewer must respond to the fact that these experiences passed through their subjects as something real without coalescing into memories to be stored or forgotten. Such experiences, and such images, cannot simply be seen and understood; they require a different response: they must be witnessed”

(Baer, 2005 p.13)

When I look through the pages of The Restoration Will by Mayumi Suzuki, I think about this act of witnessing, both in terms of the physical making of the book, but also for myself as a more remote recipient of these images. Suzuki created the book as a personal response to great tragedy; the loss of both of her parents in the Great Eastern Japanese Earthquake and Tsunami of 2011. Suzuki was a latecomer to the cataclysmic event that obliterated her hometown of Onagawa. In combing the rubble of her photographer father’s studio, she found one of his cameras buried in the silt. She took it up and recorded the aftermath.

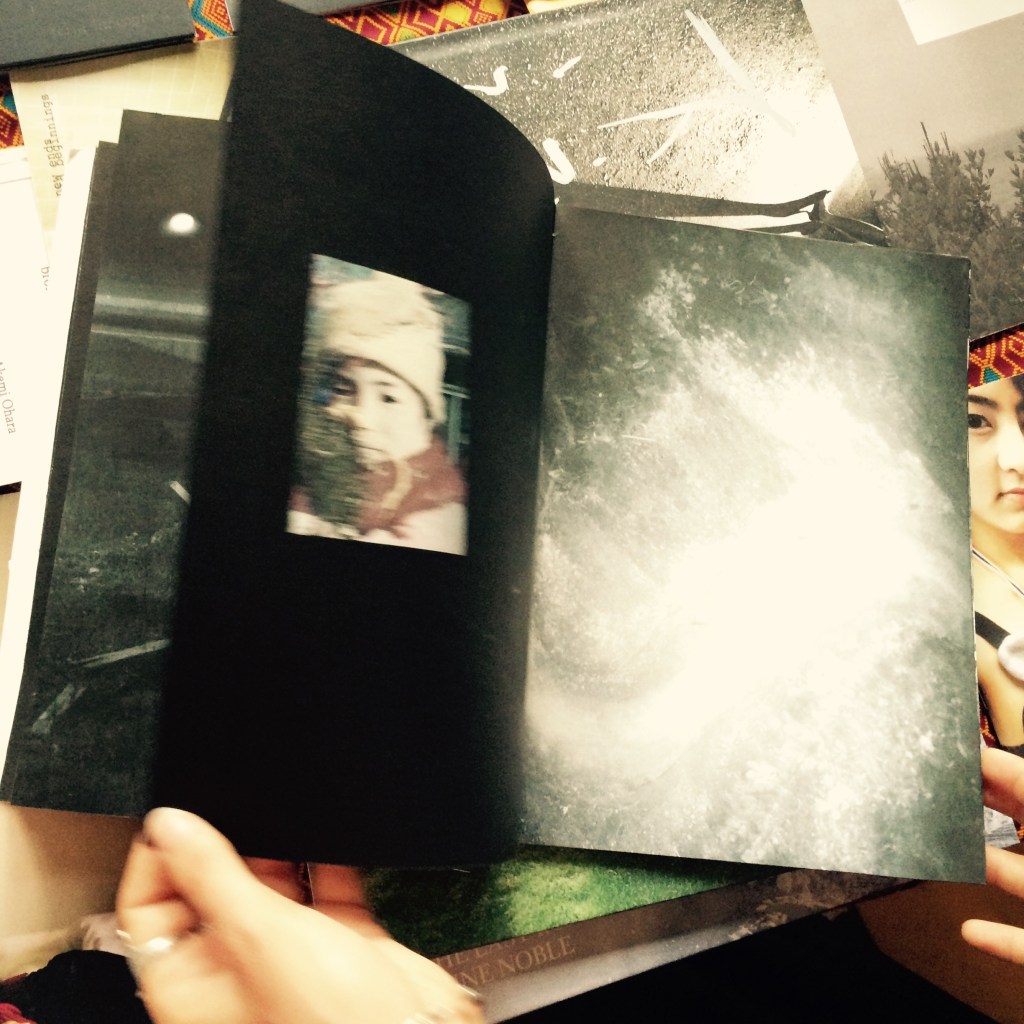

The Restoration Will begins by flowing between transcripts of desperate telephone calls, images from Suzuki’s family archive, and deadpan colour photographs of an erased town. These narrative elements give way and are subsumed into increasingly abstract black-and-white land and seascapes. The next pages carry visions from below the surface of dark water as well as fragments of photographs, and within them is tucked a rippled booklet holding hints of photographic likenesses, water-damaged but not entirely gone. This smaller volume is bound by the thinnest black thread. A central six-page gate-folded sequence of blackness gives way to the electric blue phosphorescence of an ocean at night. Once you unfold these pages all the way out, they reveal the ghosted images of Suzuki’s parents. Is Suzuki reconciling her loss as she imagines giving her parents up to this terrible beauty? Is this a visual abstraction of unbearable grief? I oscillate between feelings of intense empathy and profound pleasure in what Suzuki has made.

A catastrophic event cracks open our protective shield of normalcy in such a terrible way that we cannot move on from it. Baer suggests that the operational structure of photography echoes that of trauma; “trapping” the shock that forces open or pierces a protective barrier, (Malabou 2012) whilst blocking its assimilation into memory. (Baer, 2005). But are there strategies we can employ to work against this re-traumatizing through making and viewing photographs? Édouard Glissant, Martinican poet and philosopher, proposes the concept of opacity as protection from the all-seeing colonial gaze. Here he is suggesting that we embrace the unknowable differences of others, while still living in good relation to them. (Glissant, 2009). In The Restoration Will the abstracted nature of these night-vision images, the ritual folding and unfolding of protective pages, can perhaps be thought of as a protective partial opacity, shielding the traumatised subject. Unbridgeable gaps in lived experience are expressed through the abstraction in Suzuki’s oceanic images, and the increasing fragmentation of their sequencing through the book. The visual poetics of partial erasure in Suzuki’s images become movements away from catastrophe, from the too-clear voyeuristic gaze; a way to turn looking into witnessing.

Becky Nunes. July 2024

Leave a comment